Afternoon’s Darkness

Somaya Critchlow

AFTERNOON’S DARKNESS

6 October – 14 December 2022

London

I observed the cracks of Peckham Rye’s yellowing grounds fill with rainwater. The outstretched grass edges deluged with muddy pools that swallow up nature’s debris. Shadow play across the light of the earth, my world contained in English indirect light, that warms and darkens the entry into harvest.

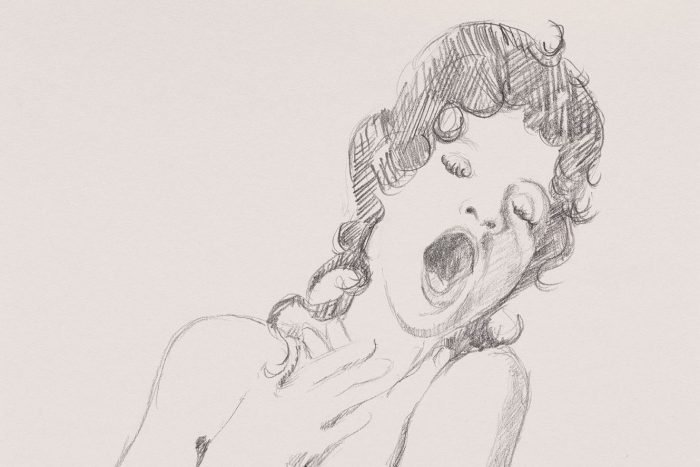

Maximillian William, London is pleased to present Afternoon’s Darkness, an exhibition of new paintings and drawings by British artist Somaya Critchlow (b. London, 1993).

Drawing on inspiration from a diverse array of resources such as the rape-revenge anime Belladonna of Sadness, the paintings of Edvard Munch, David Lynch’s Blue Velvet, and Francisco Goya’s Disasters of War prints and his studies of the Duchess of Alba, Afternoon’s Darkness draws on these chosen recourses to build its own imagery of horror and resurrection, of exclusion and creation.

Through this exhibition Critchlow continues her exploration of the female figure at the centre of painting in navigating perception, history and the complexity of image-making. The works in the show represent a shift, scaled up to what Critchlow would refer to as ‘larger mid-scale’ paintings, conceived at a time of isolation and reflection in a small seaside town through spring.

One painting in the show references The Maids by Jean Genet, which plays upon the house servant and the master-slave dichotomy. The maids are subjugated to tedious and repetitive labour that causes a hatred for their dominant mistress; within their loathing there is also hidden a fantasy for this same dichotomy of subjugation. Critchlow often presents the viewer with imagery that is burdened by its own existence, simultaneously offering up self-contained alternatives for power structures or even the possibility of ‘no good’ – just as the maids who, unable to eradicate the position they fulfil, enact the murder of their mistress.

In Critchlow’s work imagery and ideas are reproduced and reframed from a personal narrative, intimating inner thoughts, and leaving the viewer on precarious grounds.

Her work is often perceived as a commentary on sexuality, sex positivity and in turn empowerment, to a fault. It seems there is a need to position her work as actively ‘good’ or ‘positive’ instead of as an offering of autonomy. For what does it mean to be ‘good’ or ‘positive’ when it comes to depictions of the female figure?

WORKS

PRESS